PRO TIP: you only need to know 7 different kinds of EQ’s

Even though there are a million different plugins, we only have seven or eight basic kinds of EQ to work with, in the whole world of music production.

Once you get to know them, you will see that EQ's & Filters are the same no matter where you find them -- the faceplates change but the functions don't.

In this article I’m going to tell you what the basic kinds of EQ & Filter are, what they do, and how each one sounds in action.

(And starting now I'm just going to say "EQ" so I don't have to write "EQ's & Filters" every time.)

Now here's the list of EQ's that we'll talk about today.

High-Pass Filter (HPF)

Shelf Filter (High and Low)

Parametric EQ

peak-and-dip EQ (fixed frequency Parametric)

Notch Filter

Low-Pass Filter (LPF)

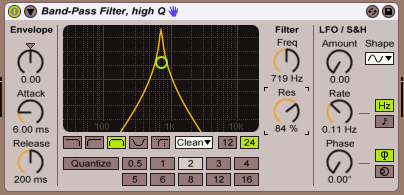

Band-Pass Filter (BPF)

graphic EQ (the one to avoid)

After you're familiar with these, you'll see them pop up all over the place -- in other DAWs, in VSTs, as synthesizer controls, on DJ mixers and mixing boards.

You'll even find them built into equipment like amps, speakers and microphones.

SO WHY DO WE HAVE SO MANY KINDS OF EQ?

Different types of EQ work with different frequency ranges.

Some EQ's can boost or cut a narrow band of frequencies in just one place (Parametric), some kinds can filter out a giant chunk of frequencies in the middle (Notch / BPF) and others work with all the lows or all the highs at once (Shelf and HPF / LPF).

Each type of EQ has its own purpose for working with sound, just like a chainsaw, a butter knife and a pair of scissors each have their own purpose for cutting physical objects.

Using EQ is a bit like painting, because the emotional effect is so colorful.

But in technical terms, think of how many different kinds of paintbrushes there are, how many shapes and sizes and uses... you have brushes, spraypaint cans, rollers, fine detail brushes, airbrushes, sponges, even your fingers for finger-painting.

They all do something different and you need to have them all on hand for different tasks.

EQ is like that, but for music instead of paint. Do not spraypaint your mixing board. This is a bad idea.

EQ IS FUN FOR PROBLEM-SOLVING

What problems does EQ solve for you?

Your mix sounds muddy

People can’t understand the lyrics in a song you're mixing

A bassline you like sounds AMAZING when you solo it, but it gets lost in the mix

you need to remove some annoying static from an audio file

the loop you like has the wrong kick drum sound

your synth Lead sounds ear-piercingly wrong

the singer's mic is picking up the bass amp on stage

THE BIG PICTURE OF EQ

In general, EQ does two things -- it takes away the stuff you don't like, and makes the rest better.

That's it.

Remove the ugly part with an EQ cut, and make the nice parts nicer with a little EQ boost.

That's really all we're doing, and everything else after that is just a refinement.

EQs & FILTERS THAT YOU ALREADY KNOW

Now that you've seen the technical names for basic EQs and Filters, let's see if we can find some places you recognize them.

You know the bass and treble knobs on a car stereo and on a home stereo, of course.

Those are low-shelf and hi-shelf Filters with fixed frequency points.

If there's a "mid" knob it's a peak-and-dip EQ at fixed frequency.

How about a DJ mixer, what do those EQ's do? The high EQ knob works like a volume knob for only high frequencies, right? That's a High-Shelf filter, same as on the home stereo.

Maybe you have kill switches? Low kill switch is a steep HPF. High kill switch is a steep LPF.

What's the mid kill switch? (wide Notch Filter)

Think about what you do on a track you love, you boost up the lows a bit, hit the highs up a little, maybe leave the mids alone or pull them down.

Everybody turns up the bass and treble and brings the midrange down a little. That's a universal effect that sounds good, and even mastering engineers do a refined version of it.

I'm sure you know a graphic EQ too, that’s the one with vertical lines and sliders.

People often make it look like the happy face, with bass and treble boosted and midrange cut.

Notice the pattern?

Even with basic EQ’s, everybody likes more bass, more high-end, and not so much midrange.

That's because -- remember -- our ears are particularly sensitive to mid-high frequencies (3-4 kHz) -- such as alarm clocks, babies crying, people screaming, fire trucks, etc.

For our ears, 3500 Hz is the sound of DANGER! Be careful with it.

Here's a Filter you don't realize that you know intimately well.

What does a voice sound like on the phone?

Is there a lot of bass? (no)

Is there a lot of high end? (no)

Telephone signals are processed with a band-pass filter (BPF) to remove everything except the vocal frequencies.

This filter makes it easier for us to understand spoken language, by cutting away everything that isn't necessary for vocal intelligibility.

It achieves this by cutting static off the top and cutting low rumble out of the bottom.

Here's a picture showing the classic "telephone preset" in EQ8, where 250hz HPF and 4 kHz LPF make a Band-Pass Filter.

You've heard this as an effect on many albums I'm sure.

FILTER AND EQ IN ACTION

Here are a few ways I create drum sounds by using Filters and EQ to cut stuff out and boost a little.

Remove the kick drum with High-Pass Filter @ 250Hz

Boost kick drum with Low Shelf @ 100Hz

Find the mud @ 130hz then cut it down

Isolate the ride cymbal with Band-Pass Filter @ 4 kHz

Remove the beep with Notch filters

Reduce snare reverb with High Shelf Filter @ 2200 Hz

Keep only kick drum with Low-Pass Filter

EQs and Filters are very powerful production tools you can use to pull sounds you like out of loops, especially in electronic music which is all about the percussion layers.

Try using EQ to re-shape your loops by frequency layers, instead of slicing them up in a Drum Rack.

EQ lets you pull out a sound like the tambourine from a full drum loop, while keeping its natural rhythm... sort of like a horizontal edit of the layers instead of a vertical edit of the timeline.

And why drive yourself crazy slicing a loop into 45 MIDI notes in a drum rack clip, if you don't really need to?

I know Live does this automatically, but Filtering loops gives you a more continuous sound, not to mention how much fun it is to play with the filters later for buildups and FX!

EQ AND FILTERS: HOW THEY ACTUALLY WORK

We'll listen to some more audio right after I talk about the controls you need to know.

EQ stands for equalization. EQ’s allow you to cut or boost the volume of a specific frequency or band of freq's.

The basic controls for EQ

Gain (db)

Frequency (Hz)

Bandwidth (Q)

Parametric EQ lets you pick the frequency and control the bandwidth as well as cutting or boosting the Gain at the frequency you chose. Three parameters. Parameter-etric. Parametric. That's where the name comes from.

Here's what they look like. Don't be intimidated. Each color of knobs is a set of controls for one bandwidth. On a big mixing console, you might have 4 sets of Parametric EQ for Lows, Low-mids, Hi-Mids and Highs (as well as a sweepable HPF).

Basic peak-and-dip EQ gives you gain control at a fixed frequency with fixed bandwidth, for example the MID knob on your DJ mixer.

You can't change the frequency it controls or the bandwidth, all you get to do is boost or cut whatever midrange it affects.

Graphic EQs are cut/boost volume sliders for a range of selected frequencies at preset bandwidths.

Technically they're a series of band-pass filters.

Here's one with the smiley face shape. Somebody did this for the photo, I doubt it would sound very good in action.

As you may notice, this is called an EQ although it's made from a bunch of filters. My point is that EQ -- or equalizing frequencies -- is really a process, while a filter is an electronic circuit.

Just so you understand the terminology, every Filter does the act of equalizing frequencies, and "an EQ" is a device that uses them.

HOW FILTERS WORK

Filters work by letting certain frequencies pass while blocking others. They allow you to remove everything above or below a certain frequency.

That point is called the cutoff frequency. Keep that term inside your brain forever: Cutoff frequency.

It's important because on many devices you won't see a knob that says "Filter", you will only see the word "cutoff" -- you need to know that THIS is the one you want.

For example, a Low-Pass Filter set at 250Hz will remove all the sound above 250Hz. It cuts off everything above 250Hz, or you could say, the cutoff frequency is 250 Hz.

Here's what that looks like.

A High-Pass Filter set at 1.2 kHz will filter out all the low end sounds up to around 1 kHz.

As you get closer to the cutoff frequency, you hear a little bit of the surrounding frequencies because cutoff frequency is not a hard limit.

There's a slope to it.

Here's a HPF with cutoff frequency at 80 Hz.

Band-Pass Filters are simply a combination of one LPF and one HPF.

When the two filters operate on the same sound, what you are left with is a band of frequencies between them.

Like on the telephone.

FILTER SLOPE

This controls how drastically the filter reduces volume of the frequencies beyond the cutoff.

Slope is measured in db per octave.

For example, if the slope says "12db/octave", it means when you measure the sound one octave away from the cutoff frequency, the volume of the sound will be lower by -12db.

For example, a LPF at 500 hz with 12db/octave slope means that when you measure the sound at 250 hz (an octave lower), it will be 12db lower than whatever level it was at 500 hz.

Octaves and frequencies are connected by 2:1 ratio. This goes all the way back to Pythagoras and the vibrating string.

But don't worry about the physics of it right now. Just think of Filter slope as "how much this filter cuts the sound."

Now, let's get back to the real world.

In EQ8 you have an option for 12 db/octave or 48 db/octave filter slopes. 48 db/octave is a steeper slope and it has the symbol "4x" in its name on the EQ8 options.

The effect of a steeper filter slope is to cut off more of the frequencies you don't want.

The following screenshot shows you both Filter slopes in Live, with LPF set to the same frequency.

You can see that the yellow line has a steeper slope than the white line.

The yellow one is the "4x" filter option which does 48db of gain reduction per octave.

The white line is the "normal" filter which does 12 db/octave of Gain reduction.

So in this example, let's imagine a sound coming through this channel that measured -6 dbFS at 1500 Hz. We will use both filters and measure the sound one octave higher, at 3000 Hz.

The 12 db/oct LPF (white line) would output -18 dbFS. The 48 db/oct LPF would output -54 dbFS at 3 kHz... a big difference!

That's the math behind why a steeper Filter sounds like a harder EQ cut.

Functionally this feels like a more precise cut at an exact frequency, which is useful when you want to interlock sounds at their own little frequency bands.

RESONANT FILTERS

So far we only talked about how Filters cut volume.

Resonance is where Filters boost.

The "Q" setting in equalizers controls the bandwidth of the frequencies you're affecting, but in a Filter the "Q" setting controls resonance.

Resonance is how much the Filter will cut or boost volume at the cutoff frequency.

It's a handy way to exaggerate the part of the sound you want.

Here's the filter section from a lovely analog synth I can't wait to get my hands on again.

The big knob on the right controls cutoff frequency and below the yellow cable you can see the resonance knob.

Resonance tends to make things sound wetter, somehow. Not wet like "dry/wet" but wet like tires on a wet street.

I know you've heard a resonant LPF in the classic 303 bassline sound.

Anyway, my point was only to say that you normally find resonance control next to cutoff frequency. They're the most popular synth parameters to play with.

Soooo, back to Q and how filters boost Gain.

In a Band-Pass Filter, Q has the effect of narrowing the bandwidth of frequencies you're affecting, and also pushing up the gain at the center frequency.

When you push it far enough, in Auto-Filter, the filter goes crazy and starts producing a screechy tone that you can sweep around by frequency.

That's called self-oscillation and it's fun, but you have to be ready for it. Strap a Limiter across the filter output before you crank up that Resonance knob.

(Q is also called resonance, remember).

In a Notch filter, High-Q makes the range of affected frequencies narrower.

Narrow Q is very useful at higher frequencies where you want to make a specific annoying sound go away (think of a De-Esser).

Here are two Notch filters with different Q settings so you can see what they look like:

FUN FACT: FILTERS SOUND BEST WHEN THEY'RE MOVING

Filters are very powerful during the technical mix process for cleaning up your sounds and cutting out the garbage that you don't want.

But they're even MORE powerful for making crazy cool sound effects.

That's why you see FabFilter, Soundtoys and AutoFilter being used as performance instruments, not just as mix tools.

If you want to have some fun right away, slap a LPF on any sound and start tweaking the frequency.

LPF Cutoff and Resonance are the two most common parameters you normally find pre-assigned for synth madness.

They're fun to play with because they are so expressive -- our emotions react strongly to a low-pass filter with changing resonance.

What's the physical-world explanation of that reaction? Ummm... as a sound goes farther away in distance, you lose the high-frequency content first... That means lowering a LPF makes a sound appear to go far away, and it means opening the LPF back up makes the sound feel like it's jumping right out in your face.

I got it! Ha. That's how we react emotionally to filtering out the highs with LPF.

EQ AND FILTER TYPES LIST

High-Pass Filter

Low Shelf EQ

Parametric EQ

Notch Filter

High Shelf EQ

Low-Pass Filter

Band-Pass Filter

High-Pass Filter (HPF)

High-Pass Filter (HPF) means only the high frequencies go past it. You use it to remove everything below the cutoff frequency.

You can use the resonance or Q control to add gain at the cutoff frequency. Lowering the Q has the effect of making the filter sloper more gentle.

Beginners sometimes find the name confusing because a high-pass filter affects low frequencies, and a low-pass filter affects high frequencies.

But anyway, HPF is one of the most important mix tools. Use it to take away all low frequency content that’s not essential for an instrument or sound.

The result is that you get TONS of extra headroom for the other sounds to come through the mix, in other words, a clean mix and a loud mix and not a muddy pile of crap.

If you want loud tracks, get friendly with HPFs.

Analog note: some mixing boards have a switch at the top of the channel strip to activate a HPF at 80 Hz or 100 Hz.

Live sound engineers will automatically click in that switch on everything except kick drum and bass guitar.

HPF is so important it gets its own switch! For comparison -- even though the LPF filter sweep is an emotionally powerful FX tool, and it's on every synth plugin you ever saw, ZERO mixing boards have a LPF.

They have high-shelf EQ but not LPF. LPF isn't necessary or essential, it's just fun.

HPF is absolutely critical, as in, cannot live without it.

Low Shelf Filter

Low Shelf Filter is used to CUT OR BOOST everything below a certain frequency.

A good example of a Shelf Filter is on the low EQ knob of a DJ mixer.

Low shelf filter is similar to a high pass filter, with one big difference.

With HPF you're trying to remove everything below the cutoff frequency but with a low shelving filter you can change all those frequencies by the same amount. It's a different concept of slope.

With low shelf EQ you can change how much you want to cut the low freq's, and you can also BOOST all the low frequencies below the frequency point.

In the picture you see a low shelf Filter boosting everything below 80hz.

At high Q values the shelf makes an opposite bump/dip around the active frequency. You'll have to experiment with that to see what it does. TMI.

Parametric EQ

Parametric EQ gives you detailed midrange control of exact frequencies.

The EQ has three controls — frequency, Gain, and bandwidth (Q).

Set the frequency (Hertz) and use the gain to add or remove volume at that Hz.

The Q setting controls how wide the range of frequencies it effects. For natural-sounding EQ, start at Q 1.5.

In general, if you are doing more than 3 dB of boost/cut you should probably narrow the Q. (Ableton "adaptive Q" does this for you).

When we say “cut before you boost” this is the EQ we're talking about.

And be careful before you turn up the Gain!

Remember fire sirens -- you don't want to crank it up at 4000Hz without warning.

Now get ready for the fat juicy part.

Stop right now and understand that you are about to hear something that will stay with you for the rest of your life.

This is the golden rule of using EQ and it's something that EVERYONE does, I mean all over the world in every studio, on every stage, in pretty much every production setting that exists, including film, video, broadcast, TV, on the moon, whatever.

THE GOLDEN RULE OF EQ

Cut before you boost.

Cut before you boost.

Cut before you boost.

Cut before you boost.

Cut before you boost.

Say it with me.

CUT. BEFORE. YOU. BOOST.

Cut means to reduce the gain of specific frequencies, like taking all the low frequencies out of a hihat sample.

Boost means to add gain, like jacking up the MIDS on a DJ mixer right before the beat drops.

Cut before you Boost.

This is INSANELY IMPORTANT to understand.

It's probably the #1 most important thing to learn about using EQ, even about mixing in general!

Remember I said that HPF is a really important? This is why. HPF is cutting out low frequencies which take up so much headroom and do nothing for sounds like snare drum. Get rid of them!

Good EQ'ing is not about only boosting up the kick drum, it's not about "warming up the mids" and it's definitely not about taking a knob and tweaking the shit out of it all the way to the top.

(That's what you do in performance on stage.)

Good EQ'ing means you get rid of the stuff that bothers our ears FIRST, before you try to sweeten up anything else in the mix. You eliminate the bass from tracks that don't need it.

Cut before you Boost.

This is the same concept of headroom that we talked about before, by the way.

You will never have enough headroom in the mix to add Gain on every channel with EQ.

You have to take things away first, by REMOVING gain at specific frequencies.

Got that?

When you remove the frequencies you don't want, you end up with more of the sound you do want. That's just the way it works.

GOOD-BYE GRAPHIC EQ

You might have noticed that I skipped over graphic EQs in this article.

There's a good reason for that.

The reason is, you don't need graphic eq for music production.

Bam. I said it. You can disagree with me but that's what I think.

Graphic EQ's (GEQ) are not very popular in the studio setting at all, in fact, because they chew up sound so harshly.

Here's a super fugly one for example.

Look at that... I can't think of a single situation where I want to boost +15db at both 40 Hz and 10 kHz. Owwwwwwch!

I've only seen one graphic EQ in a studio recently and it was being used to filter the sidechain input to a compressor -- a place you don't actually hear it.

Why did we have them in the first place?

GEQs were popular before digital signal processing existed.

They were electronically simple to build, cheap to install in many kinds of equipment, and easy for the average person to use (it's just a series of fixed-frequency band-pass filters).

Graphic EQ is really useful for tuning a sound system, correcting awful room acoustics, and removing monitor feedback.

Everybody used to connect stereo graphic EQ's between the mixer and the sound system because analog mixing boards had no EQs on the main outputs. They still don't.

But graphic EQ comes with a price, it can really destroy phase relationships and "smear" the sound all over the place. No good.

Now that modern digital mixing boards have built-in Parametric EQ on all the outputs, graphic EQ's are less and less necessary.

By the way, many modern speaker systems are actively-powered, which means the internal amps are closely matched to the speakers, not like what you encounter with a power amp and a passive speaker cabinet.

That amounts to better sound from the start and less need for corrective EQ later. Another reason you don't need GEQ.

Live sound engineers still use GEQ sometimes, and digital mixers do have graphic EQ's available, but they're more like a last resort than an essential tool.

GEQ : avoid it if you can.

REVIEW

Congratulations, you made it to the end!

Now you have a much better idea of what is going on with EQs and Filters in practice.

Look for them in all your software and hardware, and start exploring to see what you can do with a little judicious EQ usage.

Like many things in audio, when you use EQ properly nobody really notices... they just hear good music.

When you don’t use it properly however, you get a pile of problems which make everything worse.

So remember, no matter what they look like on the surface, EQ's and Filters only perform a few different functions.

Now you know what they are and you can recognize them in all the many places you meet them.

But the theory only helps if you actually USE it in your mixes!

Grab the hands-on Ableton tutorials below and put your EQ knowledge into action.